Intro

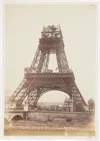

A summer’s day on Coney Island in Brooklyn. Is this a snapshot of a private outing or a deliberate aesthetic arrangement? What at first seems spontaneous looks staged on closer inspection.

We don’t know very much about this picture. Who are the people in it, and what are they gazing at out in the distance? We can only guess the answers, just as we can only guess about the anonymous photographer.

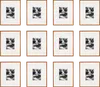

The Coney Island image was colored by hand after it was taken. Its bright palette brings to mind the work of Andy Warhol. The American artist used photos as templates for his silkscreens. In this image of Chinese leader Mao Zedong, the unusual coloring transforms a familiar photo of the Communist Party chairman and makes it strange. Does the process turn the dictator into an icon of Pop Art? Or hold him up to ridicule?

When Pop Art began to emerge in the late 1950s, it drew on images from everyday life in order to transform them in radical ways. Artists used pictures of packaged food, beverages, cigarettes, cars, and other items of mass consumerism. They also drew visual material from advertising, the press, and cinema.

Pop artists experimented with new materials, loud colors, and serial repetition in order to give this imagery an overall effect of unfamiliarity. Their works comment ironically on the consumerism of postwar society. Andy Warhol was one of the movement’s best-known representatives.

The artist creates reality. The photographer sees it.

Karl Pawek, 1963 Cited after: Karl Pawek, Das optische Zeitalter (Olten/Freiburg im Breisgau, 1963), p. 58.

The Coney Island photograph is part of the Fotosammlung Ruth und Peter Herzog (photography collection), whereas Warhol’s portrait belongs to the Kunstmuseum Basel. The two pictures meet in the exhibition The Incredible World of Photography. Seeing the two collections in dialogue opens up new perspectives on the relationship between photography and the visual arts, vistas that are as electric as they are fertile.